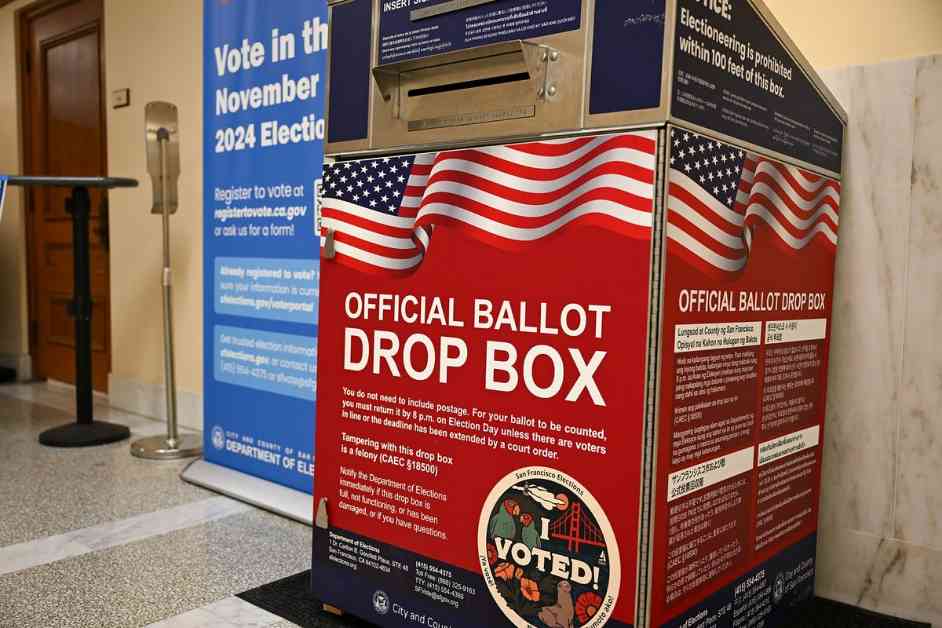

The U.S. presidential election is just around the corner, and the race between Democrat Kamala Harris and Republican Donald Trump is neck-and-neck. This trend of close elections is not unique to the United States, as seen in other democratic countries like Brexit and the Polish presidential election.

Researchers have delved into the reasons behind these close election outcomes, using mathematical models to explain the behavior of large groups of voters. Physicists Olivier Devauchelle, Piotr Nowakowski, and Piotr Szymczak have studied electoral results from 1990 onwards and identified a mechanism that can explain why elections tend to be so close.

One example is the Brexit decision in 2016, where polling data showed a close race even though initial polls favored the “remainers” by a significant margin. Similarly, in the Polish presidential election in 2020, President Andrzej Duda was ahead in the polls but only won by a slim margin on election day.

To understand this phenomenon mathematically, researchers used the Ising model, a concept from physics that simulates interactions between magnetic materials. In the context of elections, this model suggests that voters influence each other’s decisions, leading to a narrowing of the gap between competing candidates as election day approaches.

While the Ising model provides insights into close elections in countries with smaller populations, applying it to larger countries like the U.S. poses challenges due to the electoral college system. Despite this, the model offers a glimpse into the dynamics of voter behavior and the factors that contribute to closely contested elections.

Overall, the research sheds light on why elections often come down to the wire, with voters influencing each other’s decisions and creating a balance between competing candidates. While the outcome of the U.S. presidential election remains uncertain, one thing is clear: it will be a closely fought race that keeps the world on edge until the final results are in.